A Blank Screen

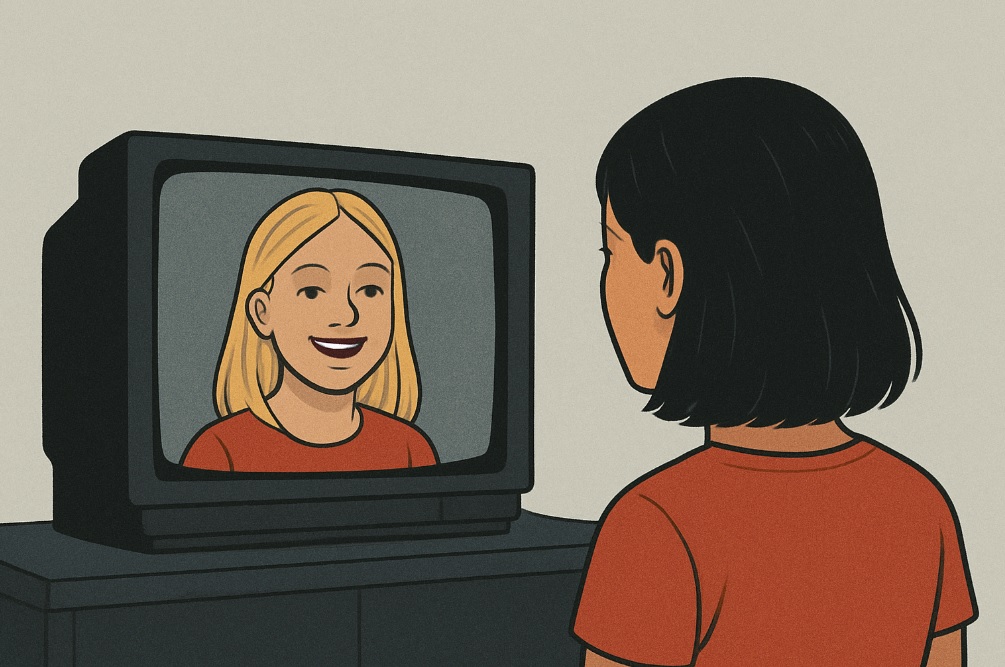

Growing up in the UK as a British-born Chinese during the 90s, one of the most pervasive yet invisible challenges was the lack of cultural reflection in the media. Whether it was children’s television, mainstream British dramas or even pop culture magazines, the absence of people who looked like me were almost non-existent. But whenever Chinese characters do appear, they are often in cameo roles either delivering lines in a thick accent, performing martial art moves or silently serving food in the background. They were never portrayed as just normal people, or multidimensional characters the way everyone else on screen seemed to be.

This absence is more than a cultural inconvenience; it quietly shapes the way you see yourself and how you think others see you. Without role models or relatable characters, you grow up without a shared cultural shorthand, without the subtle social cues that you belong here or in the way you internalise being seen as ‘foreign’ despite being born here. Mainstream media representation is often dismissed as superficial, but for children,it plays a foundational role in shaping an individual’s sense of self, their aspirations and their overall belonging within society. When the stories we consume fail to reflect our own lived experiences and identities, we struggle to find our place in society.

Growing Up Without Representation

Before the age of the internet, films and TV were shared cultural platforms for young people, they showed you who you can be, what futures are open to you and where you might fit in the world. With shows like Byker Grove, Grange Hill and Hollyoaks shaped how a generation understood British youth. Many of the shows do include a diverse cast of different ethnicities, but despite that there are almost no BESEA (British East and Southeast Asians) faces that can be seen in the shows. It was clear that the BESEA experiences were omitted from mainstream British screens.

As a result, many of us turned overseas for a sense of cultural affirmation. American media offered some glimpses of Asian American actors, comedians and filmmakers pushing their way into the mainstream figures like Lucy Liu, Mark Dacascos, George Takei and Mingna Wen just to name a few. Although Asian Americans had it better in terms of representation, they too struggled with similar issues with the representational gap growing up.

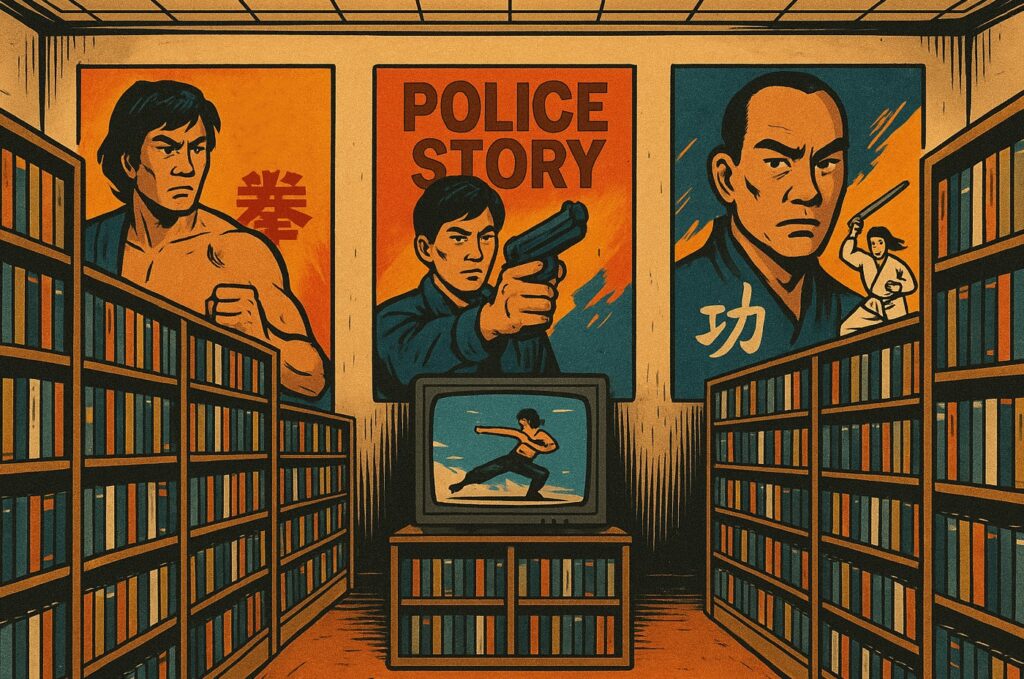

But while overseas media from Asia gave us something to hold onto, it also reinforced the gap at home. We could admire Jackie Chan or Chow Yun-Fat, but none of them resonate with the everyday reality of growing up in Britain, growing up never quite fitting into one world or the other. Without British Chinese role models in public life, integration felt like a path we had to walk alone. This invisibility led many to feel culturally displaced, not fully seen in British society, nor comfortably rooted in our heritage.

The Persistence of Stereotypes

On the rare occasions we do get excited when we see East or Southeast Asian characters appear, however their portrayals frequently conform to a narrow and stereotypical lens that have been recycled for decades. We’ve been the kung fu master, the takeaway worker, triad henchmen, the submissive geisha; reinforcing the exotic other, presented as intriguing but ultimately foreign. These caricatures reduce lived experiences to clichés, leaving little room for diversity or individuality.

These portrayals are limiting not just because they are false, but because they lack the nuance and complexity. They leave no room for realistic human experience; ESEA characters that have depth or flaws, who go through struggles or just happen to be in the pub on a Friday night. Instead, the screen offers extremes: either hyper-competent, hyper-disciplined martial artists or invisible extras. When such tropes are perpetually repeated, they cease to feel like mere stereotypes to the audience; rather, they begin to be perceived as truth.

Racial stereotypes on screen are more than lazy writing, they are a form of cultural shorthand that flattens entire communities into one-dimensional roles. In a country where ESEA communities are already perceived as “quiet” and “low-profile,” these on-screen clichés reinforce the idea that we should stay that way. Worse still, they shape how wider society perceives us, reinforcing narrow assumptions and fuelling everyday prejudice. When stereotypes dominate representation, they don’t just misinform audiences, they also deny minority communities of being seen as normal human beans.

Psychological Effects of Media Invisibility and Stereotypes

The absence of British Chinese and East Asians visibility in mainstream media has not only created a cultural blind spot but has also fostered a psychological one. When you rarely, if ever, see your identity reflected in public life, it subtly erodes your sense of belonging. Over time, this can result in what psychologists describe as internalised marginalisation — the process of unconsciously absorbing negative or reductive ideas about your own group. Research conducted by Dr. Hsiu-Lan Cheng from the University of San Francisco has demonstrated that internalised racism, often stemming from societal views that devalue one’s culture, directly impacts self-esteem. Without media visibility to affirm British Chinese identity, many young people unconsciously learned to see their heritage as a source of shame, not pride.

The long-term effects can be subtle but profound. It shapes how visible we allow ourselves to be, how loudly we speak and how much we feel entitled to belong. Educator Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop wrote that media representation is akin to both a mirror and a window. But for British Chinese children, mirrors were almost non-existent. When your identity is absent from the cultural imagination or only present in limited negative forms, it can cause you to develop self-doubt and imposter syndrome. Leading you to view your identity not as a source of pride, but as an obstacle to social acceptance.

When entire communities internalise this outlook, the consequences transcend the personal realm, becoming collective in nature. The normalisation of such stereotypes can lead to a pervasive sense of self-doubt and a stifle of one’s authentic voice. Addressing and challenging these media-perpetuated stereotypes is crucial in fostering an inclusive social environment.

Comparisons with Other Ethnic Minority Representation

In comparison, other ethnic minority communities in the UK have achieved far greater visibility in mainstream media than the ESEA community. British South Asian representation, for example, has grown steadily since the 1980s, with notable visibility in shows like EastEnders, Goodness Gracious Me and Citizen Khan. British Black representation, while still struggling against stereotyping, has also made significant cultural impact through music, sports, comedy and television with recognisable household names, from Idris Elba to Mo Gilligan, helping to cement their place in the public domain.

By contrast, the British Chinese and wider ESEA presence remains inconsistent, still relegated to token background roles or presented in heavily stereotyped ways. There is a notable absence of soap opera family or mainstream sitcom centering ESEA characters, and few ESEA presenters or journalists in prime-time slots. This disparity matters because when communities are visible in the national cultural sphere, they can effectively challenge prejudice and stereotypes. According to the Diamond Diversity Report in 2020 (by the Creative Diversity Network) East Asians only account for 1.5 % of on screen appearance, which is much lower compared to South Asians (5.6%) and Black People (6.6%).

New Faces in the Spotlight

BESEA stars: (L to R) Gemma Chan, Benedict Wong, beabadoobee

In recent years, we have begun to see a slow but welcoming shift. British-born ESEA talents such as Gemma Chan, Benedict Wong, Henry Golding and beabadoobee are making significant strides in mainstream culture, breaking through the invisibility that characterised in the earlier decade. Gemma Chan’s presence in global blockbusters and her advocacy for diversity signals to younger generations that East Asians can be both leading actors and public voices. Benedict Wong, long a respected character actor, has become renown through roles in Marvel films, providing representation in genres where East Asians were previously overlooked or confined to minor roles. Meanwhile, beabadoobee’s rise in the music industry provides a different kind of role model — a British Filipino artist whose success stems from authenticity rather than stereotype. Organisations such as Wearebeats and Rising Waves have played a great part in supporting ESEA talents and artists breaking into the creative industry.

The visibility of these figures matters because it plants the idea, especially in younger audiences, that British East and Southeast Asians belong in the cultural conversation in modern UK. For children growing up now, seeing someone who resembles them on stage, on screen or on magazine covers may normalise their sense of belonging in ways previous generations never experienced. While representation alone cannot solve inequalities within the industries overnight, the emergence of these voices signals a cultural turning point. The more these stories are told, the more expansive and varied the possibilities become for those who follow.

A Mirror in the Making

It is crucial to recognise the profound implications of media representation, or the lack thereof, on the development of individual and collective identity. By ensuring the presence of diverse, relatable characters and role models in the stories we share and consume, we can cultivate a greater sense of belonging, empowerment and cultural cohesion, particularly among younger generations. This, in turn, can lead to the development of a more inclusive and equitable society that accurately reflects modern British life, where all individuals feel seen, heard and valued for their unique experiences.

However, true representation isn’t about tokenism or fulfilling diversity quotas. The objective ahead is not simply to increase the number of ESEA faces on screen, but to deepen the quality of those portrayals. Our lives are just as complex, mundane, joyful and worthy as anyone else’s. We need ESEA characters whose stories aren’t solely centred on immigration, trauma, or cultural conflict; who instead get to inhabit romantic comedies, crime thrillers, kitchen-sink dramas and everything in between. Representation should feel natural, not exceptional and there’s still a long way to go.