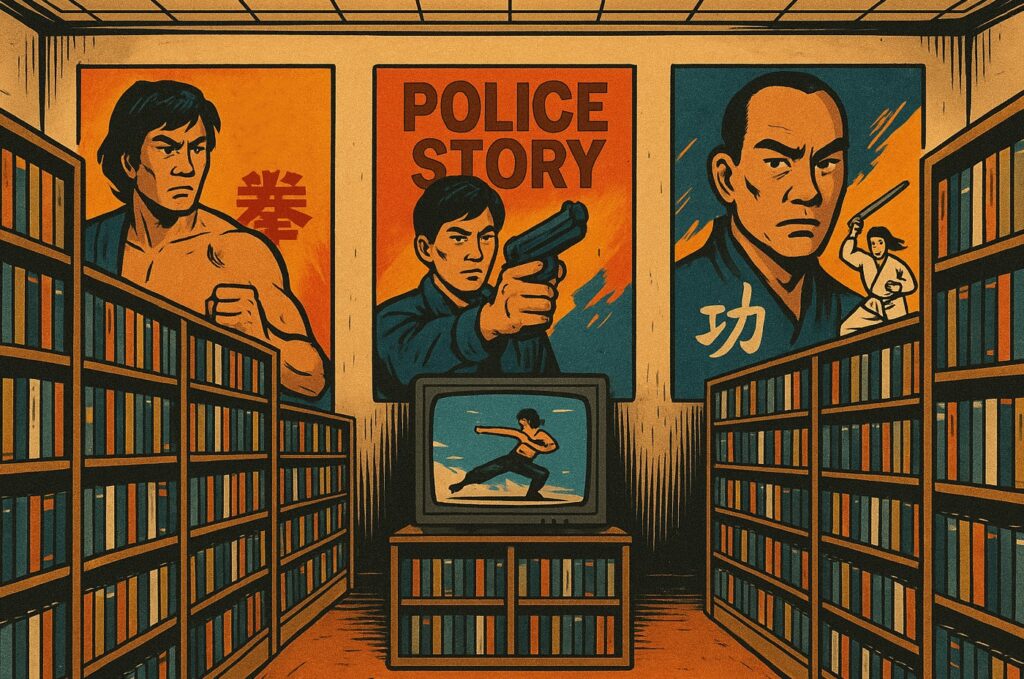

Back in the days, a trip to Manchester’s Chinatown always meant popping into the video rental store before heading home. I remember there was an entryway tucked between a restaurant and a supermarket where you go down a flight of stairs before you reach the entrance. There was nothing glamorous about it: faded posters curling at the edges, handwritten labels scrawled in both Chinese and English, and a large TVB sign hanging by the entrance.

I can still smell the faint must of plastic and paper card cases, hearing the sound of customers browsing through a stack of VHS tapes on the shelves. Stepping into the video rental store on a Sunday afternoon felt like entering a secret world, one where Hong Kong gangsters, tearful TVB melodramas and kung fu action all lined side by side on cluttered shelves. But my go-to area will always be the cartoon section with a grand selection of Cantonese dubbed cartoons or anime.

The shop itself was cramped with narrow aisles formed by shelves lined up like a maze full of VHS tapes, their covers and labels worn out from years of fingers flipping through them. A tiny CRT television buzzing in the corner, usually playing the latest TVB drama show of the time. Sometimes, you can catch Anita Mui performing her latest hit on a music show or Chow Yun-fat dashing across the screen with guns blazing. These vibrant scenes were sure chaotic and oddly mesmerising.

A Portal to Home

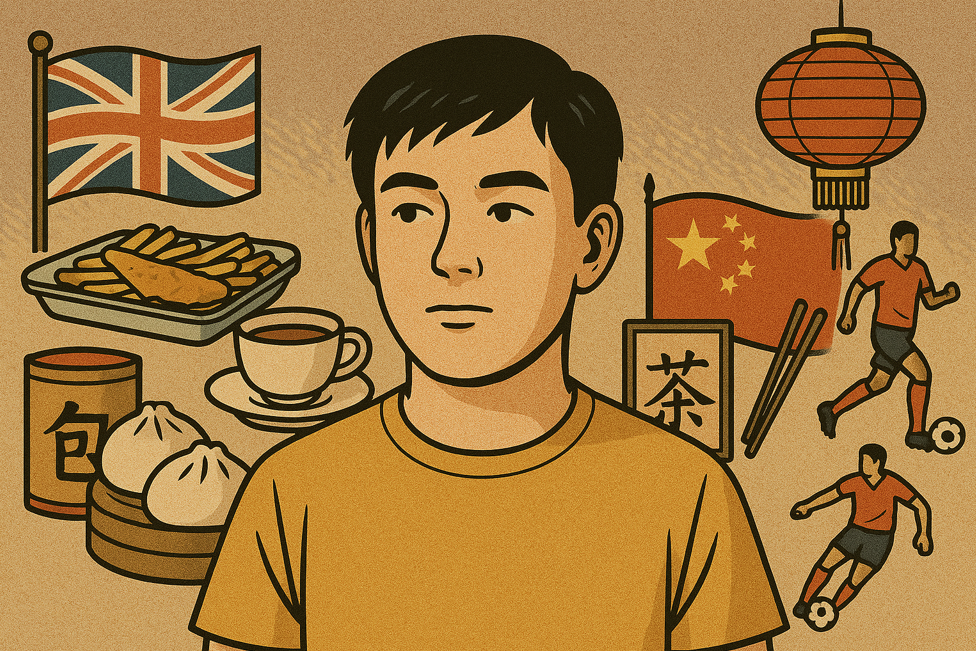

These Chinatown shops weren’t just simply renting out movies, they were part of the vibrant heart of the Chinese community. For families like mine, who had just settled and struggled to navigate life in a country that they weren’t familiar with, these little shops offered more than just entertainment. They offered a connection to our parents’ language, emotion and a sense of home that my parents remembered. To a culture that was intimate to us and yet we barely had much understanding of. The VHS tapes brought our living room a bit closer to Hong Kong, showcasing our parents’ past and heritage.

On quiet weeknights after dinner, we’d all gathered around the TV, transfixed to the images playing from the cassette tapes. Me and my siblings learnt more Cantonese from those tapes than I ever did at Sunday Chinese school, picking up the slangs through context, drama and humorous gags. But it wasn’t just simply about the language. It created many shared memories between our family. We all laughed at the jokes from Stephen Chow’s skits. The bittersweet ending from the series’ finale that got my mum all misty-eyed. These are part of the memories that shaped our childhood.

The rental store became a kind of informal social hub in itself. Sometimes, I’d catch aunties and uncles chatting, swapping recommendations or gossiping about the actors. In a way, the store was a space that unintentionally acts as an anchor for the community not just for renting out tapes, but giving the community a sense of belonging. The VHS tapes were almost like a cultural relic in itself. And for second-generation kids like me, born in the West, it was a learning experience by providing a bridge that connects us to our parents’ roots.

The End of the Analogue Era

Much like the decline of the VHS format and giant video rental stores like Blockbuster, eventually the Chinese video rental stores in Chinatowns also faced a similar fate. These smaller, community-oriented stores gradually disappeared, often without much notice. Following worldwide technological trends the old video rental business became unsustainable as many were unable to adapt to the digital transformation. It signified the end of the analogue era.

The transition from VHS to DVD in the late 1990s and early 2000s created new economic pressures for small businesses to keep up with new technology which many has struggled. At the same time, media consumption habits within the Chinese diaspora were rapidly shifting. The arrival of satellite and cable television gave access to the latest Chinese-language programming at home, often beamed directly from Hong Kong, Taiwan, or mainland China TV channels. Cutting out the need to go into a brick-and-mortar store.

The rise of piracy also played a significant factor. Bootlegged VCDs (Video Compact Discs) and later DVDs circulated widely within the community. These discs were cheaper, more portable and could contain the entire series on a few discs. They can also be copied at a drastically faster rate than VHS tapes without the loss of quality. By the mid-2000s, the internet further accelerated the decline. Peer-to-peer file sharing, torrent sites and eventually leading to dedicated streaming platforms offered on-demand access to Hong Kong films and dramas instantly at any time.

A Lost Cultural Memory

The disappearance of these shops signified the loss of not just a source of entertainment, but an end to what was once an integral part of the community. These stores functioned more than just media outlets; they served as informal cultural hubs where language, media, and memories intertwined with everyday life of many immigrants. Their disappearance marked not only the changes in the consumer trend, but a shift in how diasporic communities connect to their cultural heritage.

However it’s not simply about the loss of physical media itself, but more about the sentiment that no digital algorithm has been able to replicate. Browsing the shelves with your parents, checking out the covers to see what they were all about and asking the video store assistant for their top picks, it was like getting an education in history, the old-fashioned way. As a child, I could learn more about 1980s Hong Kong just through TV dramas and cinema than any history class. At the same time we were captivated by the onscreen presence of popular movie stars and pop idols such as; Leslie Cheung, Chow Yun Fat, Stephen Chow and Anita Mui.

Everytime I walk past the spot where the store used to be in Chinatown, it still triggers some memories. With the signage long gone and the entryway boarded up, there is no trace that it used to be a video rental store. I stood there for a moment, remembering the joy of going in as a family, getting excited by the latest releases on VHS tapes. To us British born Chinese, Chinatown’s video rental store was like a cultural museum. We didn’t simply rent movies. We also borrowed pieces of culture and nostalgia that resonated with us.