Silent Night, Takeaway Night

A typical childhood nostalgia for Christmas in Britain would mostly consist of: stockings on radiators, minced pies and crackers, the particular thrill of the days where we’re all off school. The roads empty, the shops closed and the entire nation appears to enter a warm, mulled-wine-scented slumber. But for many Chinese kids who grew up in takeaway households, Christmas was never a proper holiday. As the eve of Christmas approaches, we were also preparing for one of the busiest times of the year.

Christmas eve sets in with the glow of the heat lamps mixing with the glow of fairy lights against the tinny sound of Christmas hits on the radio. Outside in the cold weather, customers queued in their festive jumpers, grateful to find somewhere that still open in the evening. Inside all family and staff were already on standby to receive the first wave of customers of the night. A silent night for others turned into a night of chaos for us.

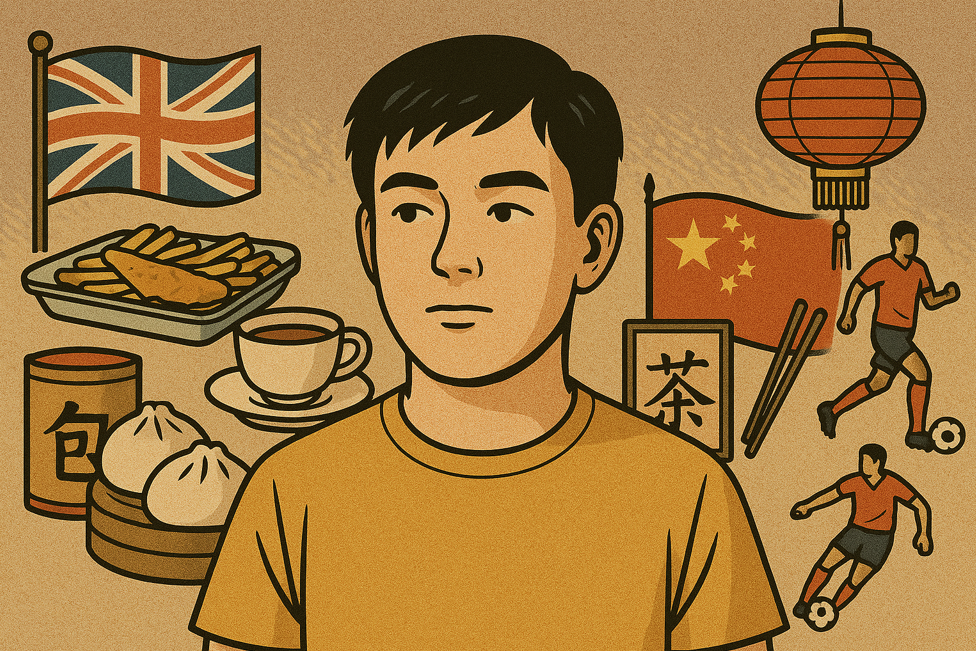

This scene reveals something profound about immigrant life and cultural integration: that traditional holidays highlight the contrast between places where individuals experience a sense of belonging and those where they remain on the outskirts. Christmas serves as a reflection of a Britain that immigrants have contributed to, even when they do not always feel fully integrated into its culture. And yet at the same time, the experience of children who grew up amongst immigrant families, Christmas is a time of both celebration and introspection, as they navigate the balance between preserving their own cultural identity and embracing local traditions.

Christmas, a Season of Business as Usual

As most families prepare for Christmas celebration; wrapping presents, last minute shop for their turkey dinner, Chinese takeaways across the UK are also preparing for their business, though the preparation looks drastically different. Instead of debating whether to make roasties in goose fat or olive oil, you’re debating whether you’ve ordered enough beansprouts and noodles to survive the onslaught of Christmas Eve. As neighbours put up their wreaths, we put up the laminated “OPEN AS USUAL” sign on the window.

For us, Christmas was more than just a holiday; it was a once a year business opportunity. It provided a chance to boost weekly revenue, reduce inventory and reassure our loyal customers that we remain dedicated to their Christmas cravings and convenience during the nation’s collective hibernation. While this may not evoke the warm and fuzzy feelings usually found in Christmas cards or the heartwarming John Lewis advertisements, it has, over time, become a cherished tradition in its own right.

An Unofficial Tradition

We have slowly realised that one of the notable aspects of growing up in a takeaway is the eventual recognition that Chinese food has subtly integrated itself into Britain’s unofficial Christmas menu. It’s oddly heartwarming to see that prawn crackers have earned a place alongside mince pies in Britain’s holiday chaos. That a carton of fried rice is, for some, as essential as Christmas crackers. Keeping up with the spirit of the season with the aroma of spring rolls and sweet and sour sauce.

And in a way, it made us part of the country’s festive ecosystem. Although not in the main dish, it serves as an appetiser before the mains of the meal. We weren’t in the Christmas films or on the Christmas cards, but we were feeding the nation when other places have closed, which, in Britain, arguably counts for even more. It is funny to reflect on this now: while we were occupied with work and observing other families incorporate their Chinese takeout into their Christmas traditions, we inadvertently established a small yet meaningful cultural tradition of our own. A tradition that derived from a cross cultural experience.

A Different Kind of Christmas Magic

As the long shift drew to a close, the fryer was finally switched off, the phone finally silent, the counter wiped clean. At long last, the much-anticipated celebration had arrived, not with a grand flourish, but with a collective sigh of relief. A late night full of leftover food, cleaning up and the rare treat of seeing our parents actually sitting down for once. It wasn’t the glossy, picture-perfect Christmas from films or adverts. But it felt real. Honest and rewarding. This small but special moment was a well-deserved reprieve from the long hard day’s work.

For many British Chinese families, especially those who grew up in takeaway households, this season can be a time of discovery, as they learn to harmonize their dual identities. As children of immigrants, we often felt like outsiders, having missed out on many cultural traditions and seasonal activities that other British kids have grown up with. However our Christmas wasn’t less magical; it was just a magic that diverges from the mainstream Hallmark template.

Caught in the peculiar in-between space: Chinese traditions at home, British customs in public and a sense of belonging that bridges two cultures that often overlook one another. And yet, within that in-betweenness, something meaningful emerged that only second-generation kids understand, and a sense of identity shaped not by what you lacked but by what you created for yourself.

And years later, looking back, those busy late-night Christmases evoke a strange mixture of emotions. There were arguments, laughter, shared exhaustion and a sense of togetherness that didn’t need tinsel or matching jumpers to make it meaningful. So perhaps the real “Christmas magic” wasn’t just about the typical festivities, but in the way we learned how to be resilient and create stronger bonds with our family.